UNDERSTANDING THE ISSUE

State of Nature

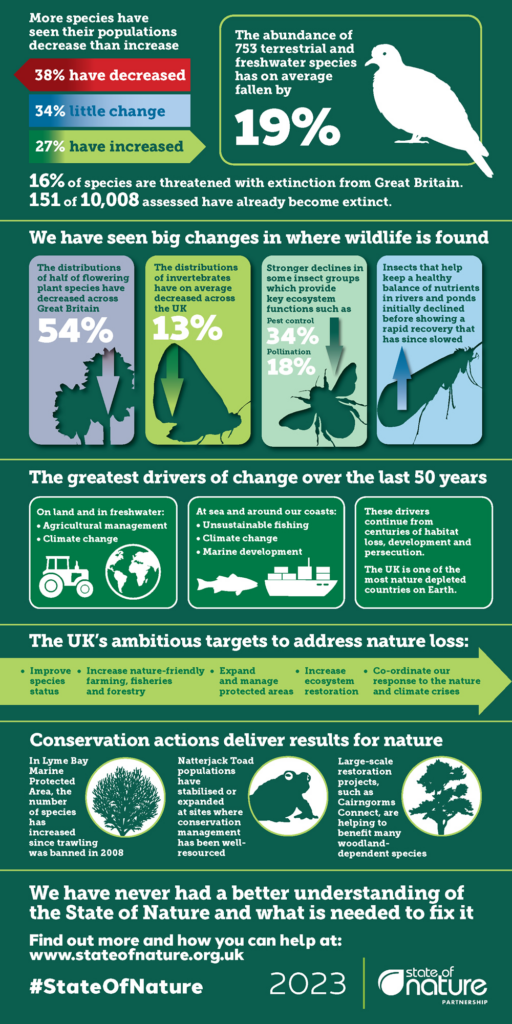

Report after report makes clear that nature in the UK is in free fall.

In 2019 the State of Nature report highlighted just how bad things had become for wildlife right here in the UK and the latest 2023 report shows that things are only getting worse. Us Brits pride ourselves on being nature lovers, we spend more per head on bird food than anyone else. Yet we live in one of the most nature depleted countries on Earth. It turns out that our green and pleasant land isn’t so pleasant after all – not if you’re a bird, a bee or a hedgehog.

Cause of Collapse

The causes of the collapse of nature are multiple but all stem back to people’s over consumption of everything from meat, fish and dairy to fossil fuels to clothes and other goods.

As humans we have destroyed the homes of our wildlife, we have taken away its food, we have disrupted the climate it evolved to cope with and we have poisoned it with chemical and plastic pollution. From the way we farm to the way we garden – wildlife has been pushed out.

To address this we need to:-

- Live more kindly and sustainably;

- Fund nature restoration

If you are fortunate enough to have some money to spare I hope that you will consider using some of that money to invest in restoring and protecting nature. This section talks about using Philanthropic Loans to fund nature – but if you are willing to donate that’s even better!

In 2021 I, started the Funding Nature project and you can read about how it all started at a place for nature and people in Dorset.

SOLUTION: FUNDING NATURE

Different type of philanthropy

Philanthropic loans are a type of philanthropy. They are an investment for impact not for financial return.

Philanthropic loans are interest-free or very low-interest loans where the lender is effectively donating the commercial return that they could make if they invested the money lent, instead of lending it to help catalyse a charitable or community project.

I hope is that philanthropic loans will be used by wealthy individuals and charitable trusts to support charitable/community benefit projects with that part of their wealth/funds which they are not prepared to give away as grants or donations.

Philanthropic loans are not intended to be used to replace donations/grants – donations/grants are very much needed to help pay off philanthropic loans.

I hope that philanthropists and charitable trusts will see philanthropic loans as a way of expanding their charitable impact beyond their donations. Philanthropic loans give you the opportunity to put money to work to help nature restoration for a while, then get it back should you need or want it either for personal, family or business reasons, or to support another project.

In the midst of the multiple crises we are facing I believe that the most effective way that I can protect my children’s future is to support action to protect safe living conditions on earth, and that includes protecting wildlife. Making a few donations isn’t enough and philanthropic loans give me a high-impact low-risk way of making that part of my money which I am not willing to give away permanently work to secure a safer future for us all.

Layered approach

Philanthropic loans work particularly well alongside donations.

For example, you could provide a philanthropic loan to fund the purchase price for a site and then a donation to cover R&D or other ‘hard to cover’ set up or development costs for the site. This layered approach is particularly helpful when trailblazing a new financial model as the first ‘test’ project takes up far more costs than those that follow.

Donations can also be used alongside loans to add value to land acquisition projects, for example to support additional engagement, evaluation, sharing of “lessons learned” or to facilitate networking. All of these add great value to the project supported by the loan but equally add costs which can be difficult to pay back through grants or other fundraising.

Debbie Tann, Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust

Wild Woodbury in Dorset was the first site acquired in my Funding Nature project and is a perfect illustration. The purchase price for the property was covered by my philanthropic loan offer. I then made donations to Dorset Wildlife Trust to cover some initial costs, like surveyor’s fees plus the cost of employing Project Manager Rob Farrington. Employing Rob before purchase of the site had even been completed paid off massively, as he was able to secure significant funding for the site through nitrate mitigation schemes, meaning that the philanthropic loan could be repaid straight after completion, freeing my money up to support the next project.

Old school philanthropy

Traditionally, charitable trusts in particular, have adopted a model of investing an endowment of funds for commercial return and then granting/donating out the income raised to support charitable projects. This means that much of the trust’s funds aren’t being used to promote their impact goals and may even be invested in corporates/sectors causing harm to the environment, wildlife and people.

In some cases charitable trusts have a legal endowment – comprised of funds that by law they need to maintain the value of. In other cases they are simply run on the basis that they will maintain a certain level of capital and donate/grant out any return that they earn on that capital.

Wealthy philanthropists have also tended to see their philanthropy in a fairly linear fashion and completely unrelated to their investments and their lifestyle choices.

With so many people and species now facing unsafe living conditions, that old school model is no longer fit for purpose.

Ethical and impact investing

Increasing understanding of the negative impact of a traditional investment portfolio has led those aware of issues affecting safe living conditions, such as dangerous climate change, to consider excluding certain types of investments (such as fossil fuels) from their portfolios.

The next step on from that is to invest in funds/listed companies helping to reduce the pollution and other conditions creating unsafe living conditions – such as companies delivering renewable energy.

Moving on from that, you can invest in start up companies developing and implementing solutions to replace the things causing unsafe living conditions, eg offering reusable solutions in place of single use.

Philanthropic loans are the ultimate step on – creating positive charitable impact directly with that part of your capital that you aren’t willing to permanently part with.

To use your wealth to help protect safe living conditions I suggest that your portfolio should include pots for all of the above as just excluding investments that cause harm isn’t the same as investing to protect life on earth.

Multiplying impact

Philanthropic Loans allow wealthy individuals and charitable trusts to directly support charitable projects with a share of that part of their funds that they aren’t willing to give away. So:-

- Instead of the traditional “invest capital – earn a return – donate return” model

- You have “loan capital – no return earned – but return effectively donated to charity” and at the same time the capital is also supporting charitable impact

- So much greater charitable impact achieved and much more quickly – exactly what we need to urgently protect safe living conditions for people and all of the other species we share our world with.

The Funding Nature Philanthropic Loan Model is:

- Flexible

- Enables quick action

- Lean and efficient

Philanthropic loans enable minimum wastage of precious funds on:

- Consultants

- Legal fees

- Admin

Your money can be matched directly to unlock a project, with minimum funds wasted on setting up complex financial return structures.

Efficiency is normally talked about in a business context, in terms of making business operations more efficient and so more cost-effective and so making more profit. But with safe living conditions threatened we need efficiency in achieving impact. We need to be focusing on how we can best use our resources to achieve impact quickly and at scale.

With this model there is no (or less) financial return. But ask yourself – do you need it? If you get a financial return from funding a nature restoration project – what are you going to do with it?

Because if the answer is – use it to achieve more impact, then in Net Impact terms you probably achieve more impact by providing a no-financial return philanthropic loan where none of your money gets wasted in setting up, marketing and administering a complex model of commoditising and monetising nature.

It’s just maths.

Say you “invest” £100k in a nature-based solution offer – funding the purchase of land to restore nature, capture carbon AND make a financial return of say 8% for you and other investors. How much of your £100k will then go on setting up all the complexity of this structure, on marketing it, on administering all the extra hoops to jump through and paying out investor returns? Will that effectively eat up your financial return (particularly once you’ve accounted for tax)? So, would your Net Impact be greater with the simpler philanthropic loan model? It’s worth at least considering.

Whilst commercial nature-based solutions investments are great for bringing in very large sums of money from investors whose focus is predominantly about achieving a financial return, and who also want to achieve a positive environmental impact, if your primary focus is impact then consider if philanthropic loans are a better option.

Catalysing land acquisition

Philanthropic loans are particularly effective in acting as a catalyst to enable and unlock projects.

Often it’s difficult to fundraise for a project such as a land acquisition until you know it’s definitely going ahead. But a charity can’t commit to go ahead until it has the money. This vicious circle has in the past led to many missed opportunities for charities and community groups to buy land.

Often when suitable land for rewilding, nature restoration and/or community food growing comes up for sale, organisations need to act quickly to be in with a chance of securing it. There isn’t time for fundraising appeals and grant applications. Plus many revenue opportunities only become available once the land is acquired.

Philanthropic loans allow charities and community groups to act quickly to put in an offer, giving them time to apply for grants, approach major donors and run traditional appeals and seek other income generating opportunities afterwards.

On top of traditional fundraising, there are already a range of ways that conservation groups can earn money from land being restored to nature, and hopefully these will increase with the introduction of Environmental Land Management schemes and other green financing mechanisms, such as the biodiversity net gain credit system in England.

Providing bridging finance

Some grant funding, for example for peat bog restoration, is only available once the restoration work has started or been completed. Without the funds to start the work the charity can’t access the grant funding. A philanthropic loan to cover starting/carrying out the work can unlock that grant funding and massively amplify and speed up the work and impact that the charity can achieve.

Equally, a community energy company may be unable to start work on installing solar panels on a school or community building until it has raised money to cover the cost of the work through a community share offer. A bridging loan for cashflow can help speed up transition to renewables by enabling the community energy company to install the solar panels first and then issue shares to repay the loan.

Keeping the money in circulation

For myself and some other philanthropic lenders, it’s really important that we can keep re-circulating our money to facilitate and unlock further projects. We place our trust in borrower organisations to focus on repaying the loans asap so that other projects can be unlocked by our philanthropic loans.

As a philanthropic loan borrower it’s essential that you play your part in maximising overall impact by doing all that you can to repay the philanthropic loan asap so that the funds can be circled on to the next project.

Philanthropic lending in practice

By the end of 2023 over 5000 acres had been restored to nature and people through the Funding Nature project and new sites are still being added – even if we don’t manage to add them to this page.

In some cases just the offer of a loan enabled a charity to put an offer in on the land, or investigate doing so, and other funding was then secured before the loan was actually needed.

The length of time for which a loan has been needed has varied from less than a month to several years. In all cases the model has played a vital role in enabling acquisitions to restore land to nature and people.

IMPACT ACHIEVED

Acquisition Highlights

Wild Woodbury

Location: Bere Regis, Dorset

Acquired by Dorset Wildlife Trust June 2021 – 420 acres (around 230 football pitches) View more

Pentwyn

Location: Mid-Wales

Acquired by Radnorshire Wildlife Trust October 2021 – 167 acres View more

Strawberry Hill

Location: Bedfordshire

Acquired by Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire & Northamptonshire Wildlife Trust August 2022 – 375 acres – View more

See more acquisitions here

Interactive Map

HELP FUND NATURE

An alternative to buying land yourself to rewild

If you are considering buying land yourself to rewild that’s great. However, here’s some advantages of instead helping a Wildlife Trust or other conservation charity to buy land as a major donor or philanthropic lender:

- Wildlife Trusts and other existing conservation charities have the expertise to help nature along and carry out baseline studies and research to record how nature recovers as natural processes are allowed to take the lead.

- The conservation group (and not you) will be responsible for insuring the land and managing any public liability and anti-social behaviour issues.

- If you want to be involved in ongoing plans for the land, you can do so as a volunteer or by taking part in a steering group or similar. You then have the flexibility to devote as much or as little time going forward as you wish – giving you the ability to support multiple projects.

- The conservation charity can access further funds to develop and manage the site, plus volunteers to help manage the land e.g. clearing invasive non-native species. Pulling up rhododendrons can soon become a never-ending chore!

- The land will be protected for nature and people beyond your lifetime.

If you own land yourself, you are responsible for managing that land and dealing with any issues that arise. There have been many occasions when I’ve been extremely relieved that it is Dorset Wildlife Trust that owns and manages Wild Woodbury, and not me, including when the Dorset Wildlife Trust team have had to deal with felling trees due to ash die-back, clearing rat-infested buildings, dealing with abuse from trespassers on trail bikes and disposing of a pig carcass fly-tipped in one of their deep ditches.

Rob Stoneman from The Wildlife Trusts explains some of the issues to consider when managing land long term:

“Having worked for four Wildlife Trusts who manage a wonderful set of nature reserves, I can appreciate some of the ups and downs of managing land for the long term. On the one hand, managing nature reserves is a complete delight – their beauty, their wonderful wildlife, the seasonality and also their deep rootedness in local communities. We mostly work with local volunteer groups that tie the reserve back to the community it serves – part of their greenspace that makes all of our lives better.

On the other hand, managing land can be tricky with much to navigate. You have to be good neighbours and neighbours do not always behave reasonably, and land can be abused – littering, dog mess, fly-tipping, ‘night-time’ activities (to be polite), illegal hunts are all examples. Likewise, navigating a path through the bureaucracy of land management can be a juggle between the sometimes competing interests of internal drainage boards, the Environment Agency, Natural England, Rural Land Registry, Rural Payments Agency, Health and Safety Executive, archaeologists, footpath officers and the dreaded ‘no-fee/no-claim solicitors’ to name but a few. None of these issues outweigh the delight of nature reserves but you have to be set up well to thread your way through.

Likewise, land is ‘forever’, in perpetuity…….and that needs very stable and long-term organisations to manage them. The Wildlife Trusts for example have been around since 1912. As local organisations we remain highly rooted in our local communities but work together in a Federation to give us the scale advantages of a 3,500-staff, 77,000-volunteer, £180 million organisation. We won’t let any one Wildlife Trust fail, providing support when required to ensure that all Wildlife Trusts are managerially and financially sound. In short, the Wildlife Trusts are here to stay, providing that ‘in perpetuity’ management of the land we care for.”

All the joy without the hassle

So in essence, helping a Wildlife Trust or other charity buy land as a major donor or philanthropic lender can give you all the joy and impact of buying and restoring land yourself without all the headaches.

You can commemorate a loved one or your personal involvement in a project to acquire land by a range of means which have a personal resonance for you. Examples include wooden carvings, tree planting, benches and plaques on site.

I commissioned a wooden sculpture of my father and 2 sons which sits in a special area of Wild Woodbury dedicated to recognising the special relationship between grandparents and their grandchildren. Next to the sculpture is a bench bearing the words “Young and old – we come together to restore wild”

Watch a short film, Making Wild Woodbury, by volunteer Susan Western, to see nature taking back its rightful place at Wild Woodbury here.

Help fund nature

Contact Dan Pescod dpescod@wildlifetrusts.org or Debbie Johnson djohnson@wildlifetrusts.org if you are interested in helping to Fund Nature as a major donor or a philanthropic lender. And get more information on their website here.

Set up a new organisation

I was a solicitor by profession and specialised in working with charities and so I’m very aware of the costs and red tape involved in setting up and running a new charity/organisation.

I’m passionate about trying to ensure that funds raised go as much as possible to the cause (such as land acquisition) and don’t get wasted on set up and management costs and red tape. That’s why my first preference is to support existing established conservation groups like The Wildlife Trusts, the RSPB and Somerset Wildlands.

So if some land comes up locally that you think should be restored to nature and people, consider first exploring whether an established local group such as your local Wildlife Trust or the RSPB etc can be persuaded to buy it with your help to fundraise. You can then also help add to the diversity of voices within those organisations.

Of course, if those groups are not able to help acquire the land you have in your sights then absolutely see if you can get a community acquisition going. Please remember that charities have to weigh up the best/greatest overall benefit that can be achieved with their funds. So whilst a small local site may be incredibly important to those living near it – acquiring it may not be the best use of funds for a charity trying to achieve maximum national/area-wide impact.

What if you just leave it? (Podcast)

Listen to Julia chatting to Dr. Sam Rose about her Funding Nature project and much more.

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/episode/2RNE6Gn36lhSnnkv0VWsDq?si=wnb3JPhDTpCGBNlfvshleA

Join me in Funding Nature and climate action

I work with The Wildlife Trusts to promote Funding Nature through major donors and philanthropic lenders helping to restore land to nature and people.

I have already been joined by others willing to invest in their future (and that of our young people) as a major donor or by making philanthropic loans available to the Wildlife Trusts and other conservation and community groups taking action on the frontline of the climate and biodiversity crisis.

If you would like to join us as a major donor or a philanthropic lender contact Dan Pescod dpescod@wildlifetrusts.org or Debbie Johnson at djohnson@wildlifetrusts.org.

What conservation groups say

“The purchase of Pentwyn Farm would simply not have been possible without philanthropic loans. The farm came up for sale in the late summer of 2021, with a closed tender bidding process. We knew there would be plenty of interest in the land so needed to act quickly. There’s much to navigate in terms of governance for an acquisition and that takes time. Philanthropic loans are very easy to engage with and give you the confidence to secure the land, and then the time to raise funds. Pentwyn is a highly strategic purchase for RWT, being adjacent and contiguous with an existing nature reserve and close to 3 others. We are now engaged in fundraising, which is progressing very well and have made great strides in developing and delivering our 30-year vision for the site.

James Hitchcock – CEO of Radnorshire Wildlife Trust

“Loans through this scheme are creating wild spaces right now. The Somerset Levels in the South West of England were once a vast wetland. From pelicans to beavers, they would have teemed with life on a scale we can scarcely imagine. Somerset Wildlands is working to bring back a bit more of that life and wildness by building up wild stepping stones in the area, acquiring patches of land to set aside for nature through rewilding. Philanthropic loans have been vital to allowing us to acquire that land, particularly in an area like this where land ownership is very diffuse, and most plots come up for sale quickly and at auction. In the face of this, the ability to quickly access the funds needed to secure lands for rewilding is essential and these loans provide an initial route to do that.”

Alasdair Cameron – Founder & Executive Director of Somerset Wildlands

“For many years Ulster Wildlife Trust, as a small local charity, has struggled to address the cash flow issues associated with buying land. Funding is normally paid in arrears, and short term philanthropic loans bridge the gap between aspiration and reality, making purchases a feasible option. This enables the charity to step up its ambition, with the loans acting as a catalyst enabling purchase of land to assist with nature’s recovery. We are in the midst of a climate and nature emergency. Philanthropic loans will also make a huge difference enabling us to scale up facilitating strategic projects, which although 100% funded have a 9-month lapse between expenditure and reimbursement. This includes peatland restoration which is critical for climate change as it reduces Green House Gas Emissions, and habitat restoration within nature recovery networks providing landscape scale conservation that is bigger, better and more joined up to reverse the declines of species.”

Jennifer Fulton – CEO of Ulster Wildlife Trust

“Tackling the nature and climate crisis needs urgent action at all levels. As locally based charities with a long history of protecting and restoring land for nature, the Wildlife Trusts are well placed to really ramp up action on nature’s recovery. Acquiring more land for rewilding, restoration and habitat creation is a priority to help wildlife recover, draw down carbon from the atmosphere and reduce pollution in our rivers and seas. With philanthropic loans alongside traditional grants and donations we can move faster and be more ambitious. With the ability to repay loans through ‘nature-based solutions’ like carbon credits, nitrate credits and biodiversity credits, we can build a business model that works for charities, for businesses and developers, for investors and for nature. Win-win!”

Debbie Tann – CEO of Hampshire & Isle of Wight Wildlife Trust

“As a very small charity, Menston Area Nature Trust would not have had the ability to purchase 20 acres of mature mixed woodland like East Wood, Weston, Near Otley, Yorkshire, in the short timescale the land was put up for sale. Although we quickly collaborated with 8 other community and environmental groups, both local and national, and raised more than £130,000 in a week, it was only a substantial loan from Julia Davies that secured the bid. We are delighted to have saved this rich habitat for perpetuity, with the opportunity it provides to improve the biodiversity of the woodland, as well as engaging people with the natural world and instilling a love and understanding of wildlife in future generations. It is hugely heart-warming to know that philanthropists such as Julia Davies exist, and are prepared to catalyse these small, but important acquisitions, protecting and enhancing nature and sequestering carbon in the fight against climate change.”

Francesca Bridgewater – Chair of Trustees, Menston Area Nature Trust

RESOURCES

Philanthropic loan resources

You can access below the resources Julia has created to try to make philanthropic lending a simple but efficient process. Feel free to use them at your own risk and obtain legal advice as appropriate. These resources are provided as an example of what Julia uses – not as legal advice and with no assurance that they are the best documents to use.

Note – as philanthropic loans involve the return of money to lenders you will need to consider money laundering regulations, obtaining ID and considering to what extent you need to ask lenders for proof of source of funds (where they got the money they are lending to your organisation to show that it’s not the proceeds of crime). What you need to do and ask for may depend on the sums involved and the extent to which you have an established relationship with the lender. If you are borrowing money to buy land your solicitor can advise on this.

Philanthropic Loan Request form for Land Acquisitions

Philanthropic Loan Request form for Non-Land Acquisition Projects

Philanthropic Loan Agreement for Land Acquisitions

Philanthropic Loan Agreement for Non-Land Acquisition Projects

Promotion & Fundraising Guidelines for Philanthropic Loans

Philanthropic loan repayment statement (to follow)

You may want to consider asking philanthropic lenders to complete a High Net Worth Investor declaration.